Imagine that you’re an astronomer conducting a radio survey of the heavens.

Maybe you’re searching for pulsars, or radio galaxies, or just mapping neutral hydrogen. Then, out of nowhere, you detect a burst of narrowband radio waves, perhaps a sequence of prime numbers that make its artificiality clear. Your eyes widen as you realize that you’ve stumbled across a signal from beings on another world.

Suddenly, whole new vistas open up in front of you. For that moment, you’re the sole bearer of profound news that could potentially transform society. It’s a heavy weight to bear. Yet scientific fame and fortune could also be just around the corner, as you will go down in history as the person who discovered aliens. You start thinking about who’s going to play you in the movie that will inevitably be make about this.

Whoa. Hold on there. You’ve discovered the signal, but before you get to the point that you’re appearing on talk shows and advising Steven Spielberg (or should it be Robert Zemeckis?) on the film adaptation, what are you supposed to do? Who do you tell that you’ve found ET? And what then? If only there was some document, some advice, to guide you through the next vital steps.

Fortunately, there is.

It’s called the Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence, often just referred to as the First SETI Protocol. It’s designed to advise scientists on the proper course of action should they make the ultimate discovery.

The Declaration’s origins go back to the 1980s, when the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) community began to think more carefully about what should happen were we to detect extraterrestrials. In 1985 Allan Goodman of Georgetown University in Washington, DC, proposed a four-step code of conduct including publicly reporting the discovery, international consultation and even giving diplomatic immunity to any aliens should they pay us a visit. These ideas developed further under the guidance of NASA’s John Billingham, who at the time was chair of the International Academy of Astronautic’s (IAA’s) Permanent SETI Committee, when he convened a special meeting about it at 1987’s International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Brighton.

The baton was then passed to Michael Michaud, a former US diplomat, who took all the disparate ideas and compiled them into the first edition of the Declaration. You can read the original manuscript on the Committee’s website.

The last major revision to the Declaration took place in 2010 (which can also be read on the IAA website). Now, it’s getting a new update under the guiding hand of the Committee, now chaired by radio astronomer Michael Garrett of Jodrell Bank Observatory at the University of Manchester.

“The protocols hadn’t been touched for 15 years, and they were out of date and didn’t reflect the environment that we work in just now,” Garrett tells Supercluster.

The dominance of social media, the rise of artificial intelligence, the broadening of SETI to focus not just on radio signals but all kinds of technosignatures, and the fact that there are far more people and organizations now either doing SETI or with a vested interest in it than ever before, have changed the playing field.

Yet there’s a deeper reason motivating the new edition of the Declaration, which is maintaining control of how a discovery is made and relayed to the wider world.

“There are so many groups around the world who are talking about this, but they’re not doing SETI, don’t have an astrophysical background and don’t know anything about technosignatures, and we want to make sure that we don’t get told by other people how they think we should be doing things, and that we take responsibility for that ourselves,” says Garrett.

Joining Garrett as author on the updated Declaration is Leslie Tennen, who is a lawyer whose specialities include international and space law.

“We’ve also got Kathryn Denning, who is an anthropologist who brings a huge historical record to this, and we have Carol Oliver who is a communication expert in Australia,” says Garrett.

Once complete, the Declaration will be voted on by the 90-plus members of the Permanent SETI Committee, who represent 14 countries. Garrett hopes this vote can take place at the IAC in Turkey in 2026, where the Declaration will also be fully presented to the public.

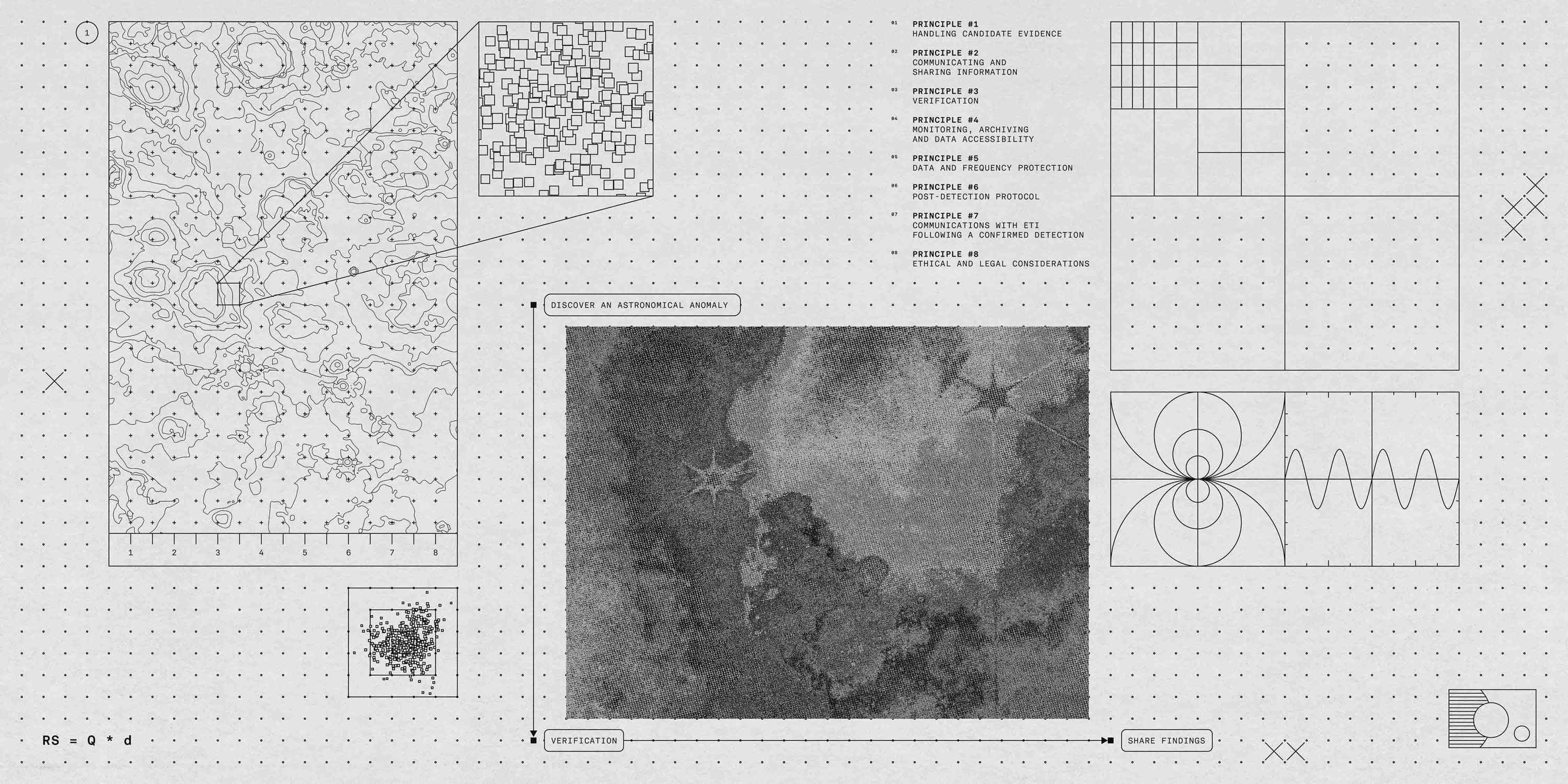

So, what’s in the Declaration? It has grown over the decades into eight individual principles.

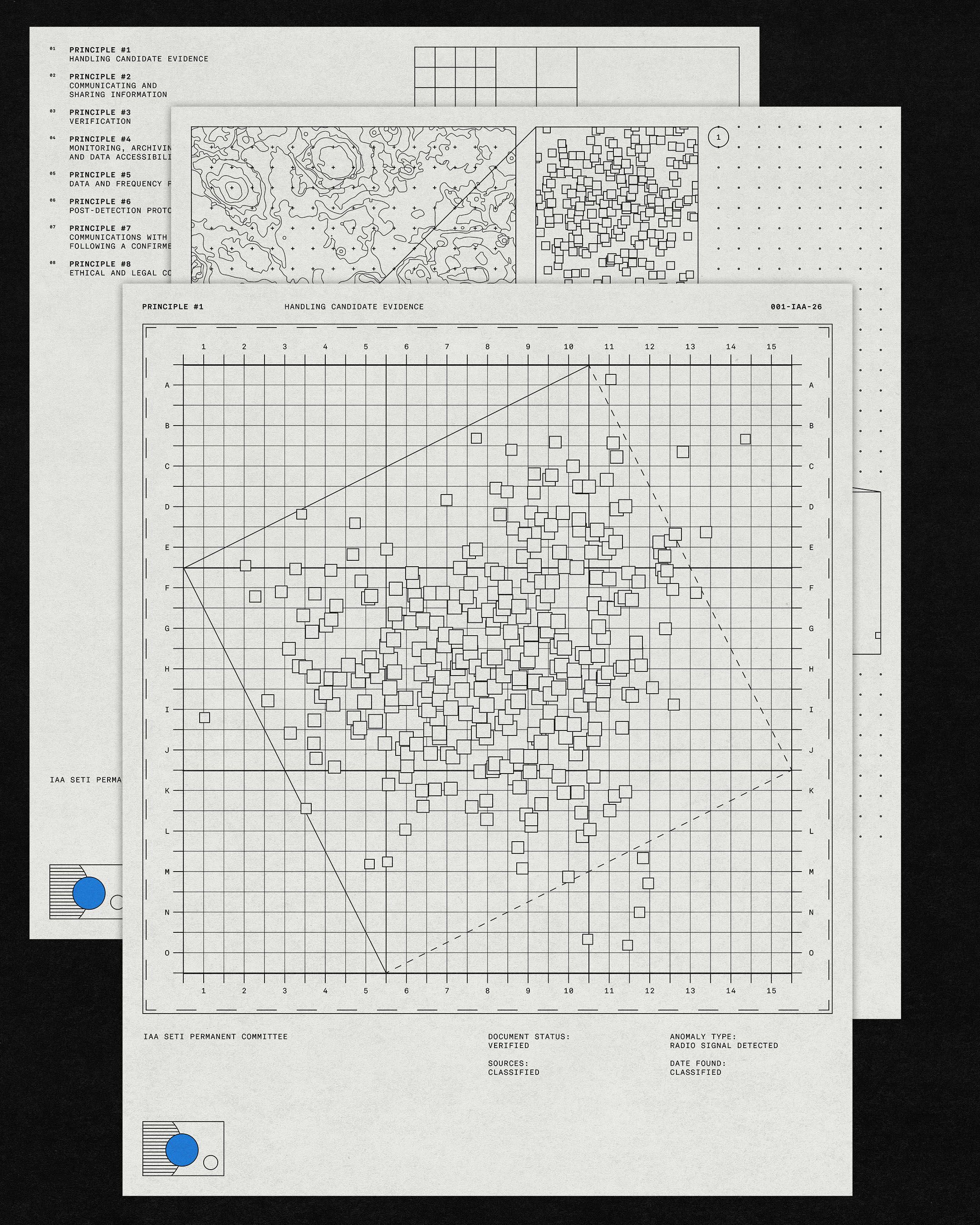

Principle 1: Handling Candidate Evidence

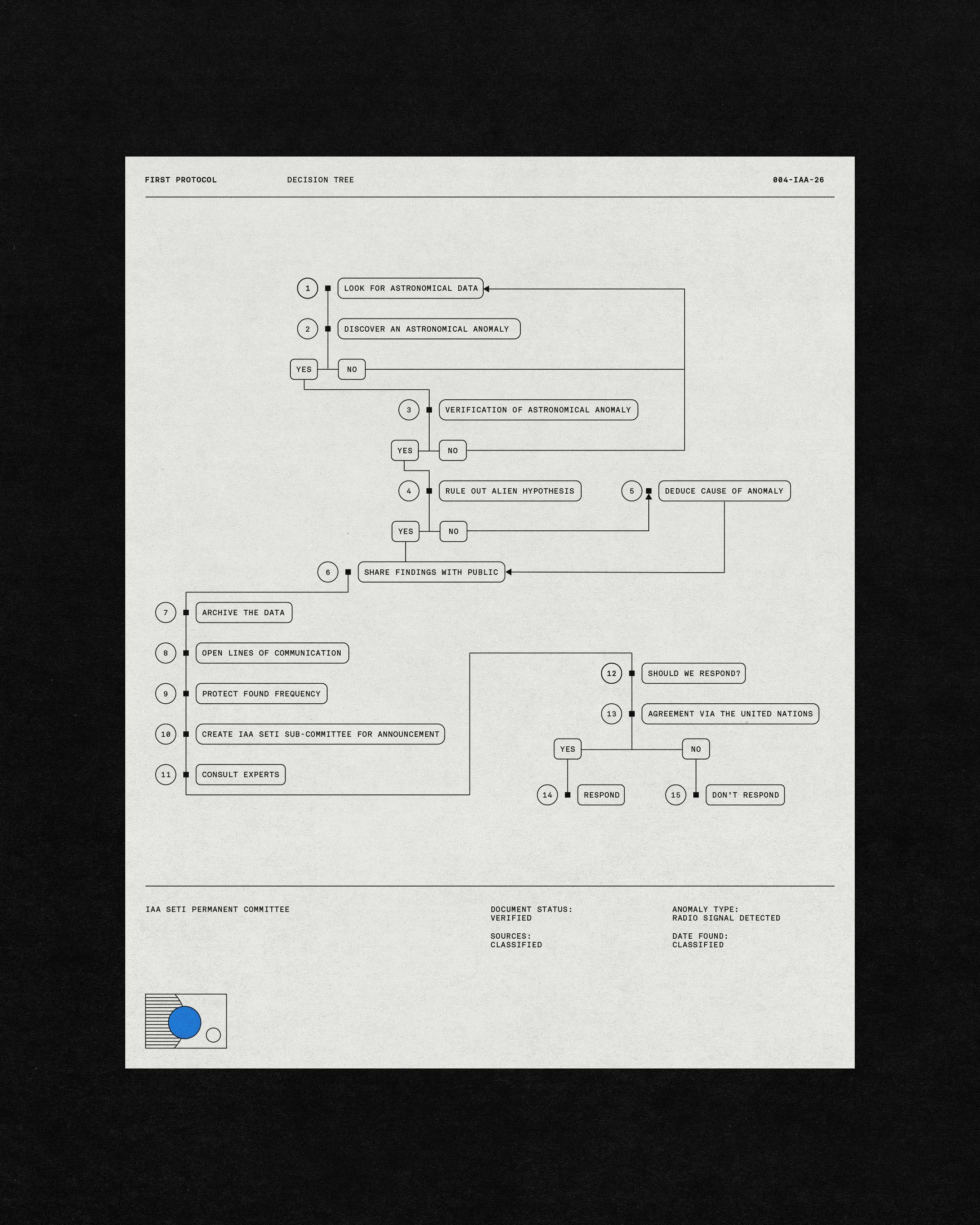

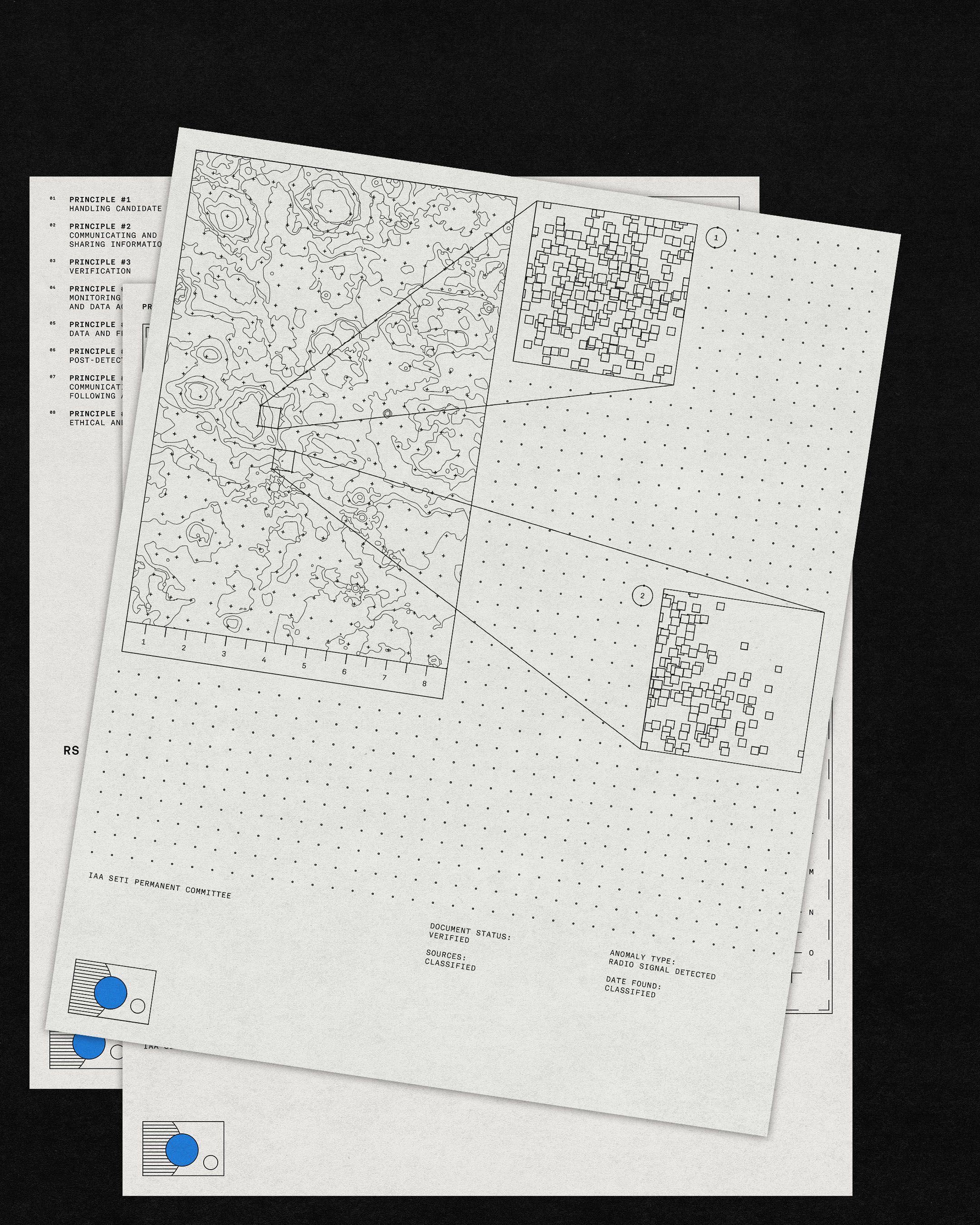

An astronomer might discover some astronomical anomaly that looks like it could be a real technosignature, but hunches and wishful thinking is not enough to declare the discovery of aliens. The first principle therefore recommends that the finding be authenticated, usually by verification from another observatory or independent group of scientists.

Verification is crucial because, frankly, it stops scientists from making fools of themselves by jumping the gun and claiming to have discovered aliens before all reasonable checks have been made. That’s why serious SETI scientists never say they have found aliens even if the evidence at first looks promising. Rather, they seek to rule out the alien hypothesis. Only when that hypothesis can withstand every test and plausible explanation they can throw at it do they start to think it could be the real deal.

“Verification is very important,” says Garrett. “People shouldn’t make any announcements until the signal has been independently verified.”

Verification requires at least one other independent organization to confirm the detection. So, for example, if a radio signal were to be detected by the Green Bank Telescope in the USA, the concern would be that could be local radio frequency interference (RFI). So another observatory elsewhere in the world, such as Jodrell Bank or Parkes in Australia, can take a look and if it too detects the signal, it’s probably not RFI. On the other hand, if it’s a technosignature hidden in astronomical data, for example should the James Webb Space Telescope discover what looks like a Dyson sphere, then verification of the analysis of that data must be performed by multiple independent groups of astronomers.

Principles 2 and 3: Communicating and Sharing Information/Verification

One of the public’s more paranoid fears about SETI is that a detection would be kept hidden from the public. In reality, current SETI policy, emphasized in this second principle, is that information should be relayed promptly and completely to the world at large once a detection has been verified. Intriguingly, the second principle states that “there is no obligation to disclose verification efforts until a discovery is confirmed.” While this makes practical sense, to avoid an embarrassing false alarm, it does imply that some secrecy may be necessary, at least at the beginning. Indeed, this has been the way that SETI has always been conducted, but things do leak. Boyajian’s Star, which is a star that experiences unusual dimming events that we now know to be caused by cosmic dust clouds, was at one time a candidate to host an alien megastructure. This astounding possibility was reported in The Atlantic before any determination of the cause had been made. Similarly, Breakthrough Listen Candidate 1 (BLC-1), which for a short time was the most promising candidate radio signal ever detected, was leaked in The Guardian before its analysis ever reached peer review. A 1997 detection of a possible signal by the SETI Institute reached the press within 24 hours, before astronomers figured out that the signal was coming from the joint NASA–ESA SOHO mission.

However, once a detection is confirmed, Garrett very strongly urges the reveal of all the information.

“I think transparency is also important, because that’s the expectation from the public,” he says. “As soon as we have something and it’s verified as clearly being a signature of intelligence, we should open up about that and tell people.”

The findings still have to be peer reviewed, after which the Declaration states that “the public, the scientific community, and the Secretary General of the United Nations” need to be briefed.

Principle 4: Monitoring, Archiving and Data Accessibility

This concerns the handling of the discovery data, which given its importance scientifically, culturally and historically, should be like handling precious treasure. Care should be given as to how the data should be archived and future-proofed, making sure that future generations can access it. For example, saving the data in MS Word might give scientists a century from now a headache if they no longer use Microsoft systems, and so formats and details of how to access those formats are vital and need to be as simple as possible. Should the data be lost and the signal never recovered, it’s not hard to imagine conspiracy theorists in the future claiming that the detection was a hoax.

Principle 5: Data and Frequency Protection

Side-by-side with how to handle the detected data is keeping the lines of communication open should anymore data become available. If it’s a radio detection, then the specific radio frequency on which the signal was detected must be protected from RFI. Astronomy in general already has some protected bands, for example the 1420MHz emission line from neutral hydrogen. The Declaration states that “international agreement should be sought to protect the appropriate frequencies by exercising the extraordinary procedures established within the International Telecommunication Union.” Because a detection is likely to be in a protected or little-used band anyway, since astronomers won’t be looking at frequencies polluted by RFI, then in theory this should be a simple matter. However, given there can overspill from local RFI, and reports that Starlink satellites are radiating in protected bands, it might not be as simple as it sounds. It would be a statement of humankind’s fragrant disregard for the environment around us if we were to allow our communication channel with another technological species be drowned out by rampant and careless interference.

Principle 6: Post-Detection Protocol

The news that we are not alone in the Universe would be profound, but that news shouldn’t be lobbed like a hand grenade into modern society while the discoverers run the other way. In fact, it’s incumbent upon scientists — physical and social — to be on hand to assuage any concerns, advise about any course of action, and inform a public who would otherwise be at the mercy of rumor and make-believe running amok in the aftermath of a successful detection.

To that end, the Declaration states that the IAA SETI Committee will maintain a post-detection sub-committee dedicated to advising in the aftermath of a successful detection.

It won’t just be astronomers trying to tell people what to do, either.

“Do we think that astronomers should be making the decisions? I certainly don’t,” says Garrett. “Once the discovery has been made it becomes a societal question. So within the committee we have communication experts, we have legal expertise, we have social scientists.”

This expertise would be available to fully communicate the discovery and its consequences to the public and politicians.

“The protocols were originally set-up because a discovery of this nature would have an impact well beyond the scientific domain, and we need to consider certain aspects of how we do our research maybe more carefully than other fields,” says Garrett.

Principle 7: Communications with ETI Following a Confirmed Detection

In every version of the Declaration one principle has remained consistent: that no reply should be sent to a message received from an extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) until there has been international consultations and agreement via the United Nations.

One issue with this is that legally there’s a lot of leeway. The United Nations could prevent anyone from sending a reply, but so far the United Nations has not issued a decree on this. Even Garrett admits that for every principle in the Declaration, “We can’t enforce anything — there’s nothing legally binding.”

This has prompted some in the SETI community to suggest that even after a confirmed detection, the celestial coordinates of the signal’s point of origin should be kept secret to prevent anyone from transmitting a reply without authorization. However, this would go against the ethos of transparency and full disclosure that the Declaration recommends.

Ultimately, it is down to the United Nations to agree, and quickly, to ban all attempts to reply until consultation has occurred and permission been given from the highest levels.

Principle 8: Ethical and Legal Considerations

The final principle is aimed at SETI researchers themselves, urging the highest standards and full cooperation with international legal authorities about disseminating the news of a discovery in a prompt and way trustworthy way.

Ultimately, the aim is to build a repository of best practice for different scenarios, and the SETI Institute has set up an initiative to help guide researchers in doing things with integrity.

Support Supercluster

Your support makes the Astronaut Database and Launch Tracker possible, and keeps all Supercluster content free.

SupportMany SETI researchers will already be familiar with the Declaration of Principles in its various guises over the years. However, the Declaration is relatively unknown in the wider astronomical community, which is a concern, says Garrett.

“The reality is that this discovery could be made by someone who’s looking for something else in the astronomical data and who finds some kind of anomaly, but who has never read this Declaration of Principles,” Garrett explains. “What we hope is that if they did make that discovery that they would feel that there is some guidance and seek out people to advise them. Hopefully the protocols will be something they can find quickly before deciding to go to the newspapers. Especially for an individual scientist, they might not have a feel for what they’re letting themselves in for, but I think the fact that we talk about safe-guarding scientists, which has not really been in the Declaration until now, would hopefully raise a red flag in their own minds about what they might be getting themselves into.”

The Second Protocol?

Earlier in the article we described the Declaration as the ‘First Protocol’, which implied that there were meant to be more. What happened?

Back in the late 1980s, Michael Michaud broke down the discussion of best practice into two broad areas: handling a detection, which is what the Declaration of Principles covers, and transmitting our own messages into space, otherwise known as Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI). This was to be the Second Protocol, but it never came to be because of disagreements that threatened to tear the SETI community apart. While some researchers passionately believe that humankind has a duty to reach out to other possible technological life in the Universe, others feel that such acts are unauthorized diplomacy that carries great risk should we initiate contact with a more technologically advanced species only for it to go wrong.

Are Garrett and the IAA SETI Committee willing to take another stab at the Second Protocol once the First Protocol is signed off?

“I personally think METI is a bit of a hot potato,” Garrett admits. “I’m wary of the fact that the last time this was attempted we had people who fell out and became quite aggressive with each other, and it was no longer a scientific argument, it was personal, and there’s no room for that on our Committee.”

That said, if the Second Protocol were to be looked at again, Garrett is confident that most of the current Committee would say that we shouldn’t be sending unsolicited messages, not least because those who conduct METI do not have the right to speak for everyone on Earth. That’s why the Declaration of Principles places the decision of whether to reply to a signal at the feet of the United Nations.

Room for Unidentified Flying Objects?

Ufology has enjoyed something of a renaissance in recent years, even though it still embodies conspiracy theories and no undeniable evidence has come to light (the footage from USAF fighter jets, while championed by many in the UFO community, are yet to convince those skeptical of alien visitation).

Nevertheless, the ufology’s increasing prominence prompts us to ask whether the IAA SETI Committee have considered including how to respond to credible UFO sightings in their Declaration of Principles.

Garrett reveals that the topic has come up for discussion among certain Committee members, but like METI, it prompted strong opinions from those for and against. To avoid arguments, Garrett stipulated that the Declaration only concern itself with signatures of extraterrestrial technology beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

“It also connects with the IAA because it’s about space, it’s above the Kármán line,” says Garrett, who adds that he doesn’t rule out considering how the Declaration could be applied to phenomena seen in Earth’s atmosphere in the future should the topic become more scientific.

The Declaration of Principles will be finalized in August 2026 at the IAC, and you can read the current draft, and how it has been constructed, in this paper. Hopefully it will raise people’s awareness of it, such that should one lucky astronomer make the ultimate discovery, they’ll know where to go to get the help they’ll need to announce that discovery to an eager and excited world.